Home » Session 2: Initiating Collaboration

Introduction to Collaborative Governance

Session 2: Initiating Collaboration

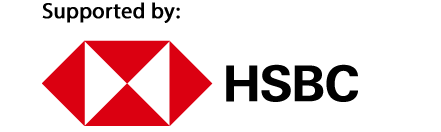

General System Context

Collaborative governance is initiated and evolves within a multi-layered context of political, legal, socioeconomic, environmental, and other influences (Emerson et al., 2011). The context shaped by the external system creates opportunities and constraints and influences the general parameters within which a CGR unfolds.

-

Institutional Environment

The institutional environment includes the broad systems of relationships that span jurisdictional areas related to a policy problem. These can directly influence the purpose, structure and outcomes of the collaborative process.

-

Dynamics in the Political Environment

Dynamics in the political environment also play a material role in formulating cross-sector collaborations. This could include power relations, where significant imbalances in power between stakeholders could create difficulties for collaboration.

-

Sector Failure

In most cases, cross-sector collaborations appear to be driven by the degree to which efforts to solve a public problem have failed. The inability for a single government unit to remedy a public policy problem instigates cross-sector collaborations, which involve different nongovernmental stakeholders that participate in carrying out a public purpose or provide effective remedies that could not otherwise be accomplished.

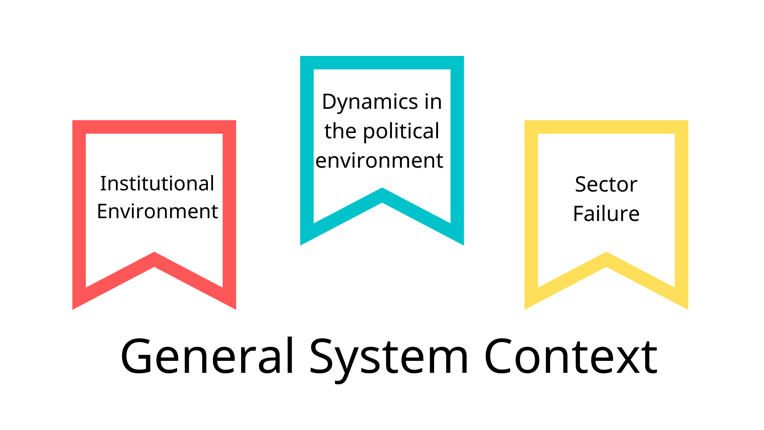

Drivers

The CGR framework separates the contextual variables from essential drivers, without which the impetus for collaboration would not successfully unfold. These drivers include leadership, consequential incentives, interdependence, and uncertainty.

-

Leadership

Leadership refers to the presence of a recognised leader who is in a position to initiate and help secure resources and support for a CGR. The leader can located anywhere, within or outside of the government. Regardless, she should possess a commitment to collaborative problem-solving and exhibit impartiality concerning the preferences of participants (Bryson et al., 2006; Selin & Chavez, 1995).

-

Consequential Incentives

Consequential incentives may be positive or negative triggers that give rise to stakeholders inducing an engagement.

-

Interdependence

As illustrated in the discussion of general system context, sector failure or the incapability of individuals to accomplish something on their own is usually the precondition for collaborative governance (Gray, 1989).

-

Uncertainty

Uncertainty arises from unobservable and stochastic environments with an unknown solution in public policy problems. More often than not, it cannot be resolved internally, individuals and groups are driven to collaborate in order to reduce, diffuse, and share risk (Emerson, et al., 2011). Collective uncertainty about how to manage societal problems is also related to the driver of interdependence.

References:

Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Stone, M. M. (2006). The design and implementation of Cross‐Sector collaborations: Propositions from the literature. Public administration review, 66, 44-55.

Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T., & Balogh, S. (2011). An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance.(June 2009), 1–29. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. https://doi. org/10.1093/jopart/mur011.

Gray, C. M., König, P., Engel, A. K., & Singer, W. (1989). Oscillatory responses in cat visual cortex exhibit inter-columnar synchronization which reflects global stimulus properties. Nature, 338(6213), 334-337.

Selin, S., & Chavez, D. (1995). Developing an evolutionary tourism partnership model. Annals of tourism research, 22(4), 844-856.

Continue to “Session 3: Collaboration Dynamics”

© 2022 Centre for Civil Society and Governance at The University of Hong Kong

Except where otherwise noted, contents of this e-study is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License.

![]()