Home » Session 1: Integrated sustainability assessment, cost benefit analysis and social return on investment

Sustainability Project Impact Assessment

Session 1: Integrated sustainability assessment, cost benefit analysis and social return on investment

Cost benefit analysis (CBA) is broadly known as a tool for the estimation of monetary values for environmental changes in which efficiency is the main concern, i.e. the gains in human well-being should always exceed its costs for a project to be approved. Under CBA, the issue of equity distribution is often neglected and proposals with the largest net benefits attract the strongest support (Atkinson & Mourato, 2008). In contrast, the integrated sustainability assessment approach adopts a more comprehensive view in measuring impacts, in which more attention is given to each stakeholders’ well-being and the larger community (e.g., the broader socio-biophysical systems, communities involved, and even regional and global integration) instead of a net calculated benefit, and improvements are sought on everyone’s behalf.

The CBA approach is critiqued for addressing the loss of environmental assets simply through counter-balancing attempts. For example, by introducing shadow projects to argue that the environmental damages caused by other projects in the same portfolio are compensated for (OECD, 2006). Moreover, the calculation in CBA discounts future benefits (or costs) by attaching a lower weight to them when compared to the present (Atkinson & Mourato, 2008). Consequently, environmental problems, which often have a longer time horizon, are overlooked. Opposed to the tenuous application of the sustainability concept in traditional CBA, the integrated sustainability assessment is developed surrounding the core dimensions of sustainability, focusing on the enhancement of capacities of both the present community and the future generations.

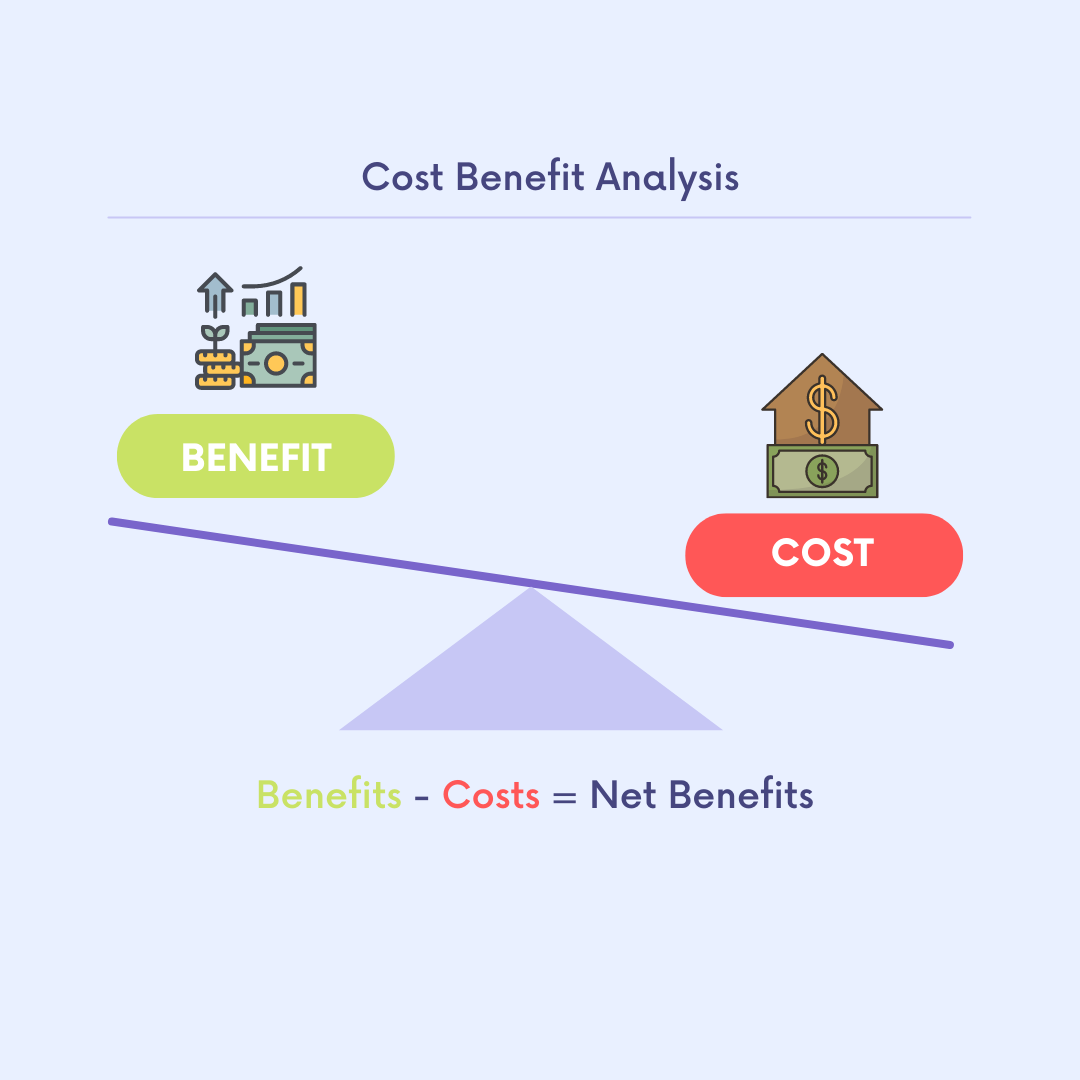

The social return on investment (SROI) approach is a framework for measuring the broader concepts of values created by an organisation or an activity (The SROI Network, 2012). The major target of measurement is the changes that are relevant to the stakeholders (people that contributed to or experienced the change). The measurement is often expressed in a ratio (benefit: cost) with monetary values as a representation for all kinds of social, environmental, and economic outcomes. The SROI follows an impact map (or theory of change, which will be explained in session 3) by recording the inputs, outputs and outcomes. The financial values assigned to these inputs and outputs would take reference from financial proxies (which vary by contexts and research). SROI is particularly concerned with the input-outcome causal relation and hopes to eliminate deadweights and any outcomes that cannot be attributed to the project evaluated.

Source: The Tangata Whenua, Community & Voluntary Sector Research Centre,

New Zealand (https://whatworks.org.nz/social-return-on-investment/)

YouTube link: https://youtu.be/l3CWpt49maw

Though the integrated sustainability assessment approach may resemble SROI in some instances, there are several distinguishing features among them. While SROI captures a broader concept of value by including considerations of wider social circumstances, ultimately, the values are monetised. For non-market values, since there is no standard code on what financial proxies to adopt, the changes created by the project may not be accurately reflected in the assessment (Yates & Marra, 2017). In contrast, the integrated sustainability assessment measures changes by focusing on issues raised by stakeholders and construct suitable indicators accordingly. Non-market or intangible values, such as knowledge enhancement, solution development, cultural heritage, etc. can therefore be better captured in its original nature than through a financial proxy.

Another difference between SROI and an integrated sustainability assessment is the weight of emphasis placed on causal claims. As aforementioned, SROI emphasises the causal relationship between inputs, outputs and outcomes, and take benchmarks, counterfactuals, attribution and displacement issues into consideration. Under the SROI framework, outcomes only consist of direct or indirect changes in stakeholders’ lives, and the stakeholders included must experience changes that are related to the activity (The SROI Network, 2012). The integrated sustainable assessment approach takes into account more far-reaching impacts, e.g. the development of an innovative solution that may benefit the entire industry in a long run. Longer-term impacts would also be included in the assessment of the activity, even if there is no salient causal linkage between the project evaluated and a much broader impact (e.g. climate change mitigation or general public education). In other words, SROI may be stricter in making causal claims, while an integrated sustainable assessment is more inclusive.

Resources

Atkinson, G., & Mourato, S. (2008). Environmental Cost-Benefit Analysis. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 33(1), 317–344. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.environ.33.020107.112927

Nicholls, J., Lawlor, E., Neitzert, E., Goodspeed, T., & Cupitt, S. (2012). A guide to social return on investment: The SROI network. Accounting for Value. Available at https://socialvalueuk.org/resource/a-guide-to-social-return-on-investment-2012/

OECD (2006). Cost-benefit analysis and the environment: Recent developments. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Rotmans, J. (2006). Tools for Integrated Sustainability Assessment: a two-track approach. Integrated Assessment, 6(4), 35-57.

Yates, B. T., & Marra, M. (2017). Social Return On Investment (SROI): Problems, solutions … and is SROI a good investment? Evaluation and Program Planning, 64, 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.11.009

Continue to “Session 2: Defining the objective”

© 2022 Centre for Civil Society and Governance at The University of Hong Kong

Except where otherwise noted, contents of this e-case is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License.

![]()